I was given this book by Emma: a live, face-to-face handing over of a book, which by itself is a wonderful experience that adds to the joy of reading. This book is a translation from Spanish (Matar y Guardar la Ropa) and, unfortunately, is not available in English.

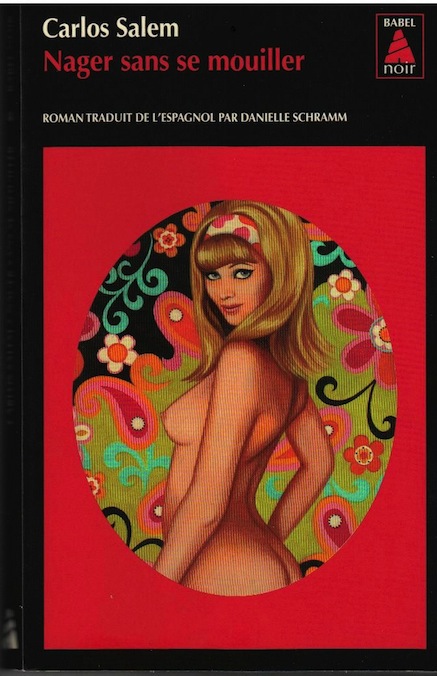

It’s part of the Babel Noir collection, a series published by Actes Sud. I’m always drawn to the books of Actes Sud: they feature a lot of foreign writers, and I like their covers, the quality of their papers and the legibility of their typeface. But back to the book.

What the reader repeatedly faces throughout the book is how often he/she is taken by surprise about some revelations through simple but quite smart technical maneuvers by Salem. For example, the opening couple of pages present to us a less-than-average Juan, our narrator, taking the elevator of some fancy building together with a cigar-smoking gentleman, a woman and her daughter. He ridicules his curbed posture and realizes what little impression he must make on the woman; a self-derision of 4 pages that ends with the woman and her daughter leaving the elevator leaving me with a dumbfounded look on my face when our unremarkable Juan draws a gun clad with a silencer and shoots our cigar-smoking gentleman right in the forehead. Of course, because it came as a complete surprise to me (not having read the synopsis), I had to re-read the shooting paragraph because I assumed that it was the gentleman who ought to have shot our Juan Perez Perez.

As by now you might suspect, JPP aka Number 3, is a hitman working for a mysterious Enterprise, whose agents are similarly identified by their numbers, receiving targets to be liquidated from the equally mysterious Number 2. Undoubtedly, the reader will be tempted to compared and judge the story against other spy novels but Salem spares us this. Though JPP undertakes trainings, learns manuals and goes through specific procedures before delivering the packages, the codename for liquidating the targets, Salem belittles their significance while going through their technical details. On the one hand, he evades the trap of cheap parody while being humorous and preserving the plausibility of the situation. He employs the same technique with the flashbacks that JPP reveals to us during his apprenticeship under the older Number 3, who dispenses hitman wisdom and tactics to the young JPP while coming up with his own self-proclaimed axioms such as: “Beware of girls with small breasts”.

Humor is omnipresent throughout the book, and a naughty humor at that that made me crack up every couple of pages. For our JPP is sent by the Enterprise, not to deliver a package but to keep an eye on one, to a nudist colony with his 10-year old son and 15-year old daughter. Circumstances have it that he finds his tent adjacent to his ex-wife and her lover, the incorruptible judge Beltran. I’m it surprised by how easily Salem is capable of spinning jokes around this ludicrous situation throughout the book! Another coincidence at the nudist colony, is the presence of his long-lost school friend, Tony, rendered one-eyed by JPP himself in an attempt to protect his friend that went all awry, and Tony’s plastic and ice-cold girlfriend, the imposing Sofia.

Things start to get interesting when JPP is ordered to keep an eye on the owner of a car with a certain matriculation number, a car he knows quite well since it is the one he offered his wife, and which has since changed ownership to none other than Tony, his long-lost school friend. Amidst the heat of the summer, the naked bodies and his own infatuation with the beautiful Yolanda, JPP’s thoughts are all jumbled and he can’t make out what is really going on in that colony and who is after whom. The sudden appearance of another “Number” exceptionally dispatched to the colony complicate matters more and alert him that a parallel plan might be concocted by the Enterprise.

In trying to make sense of the situation he is in, Juan confronts himself, as he wonders who is he? Is he Number 3? Is he the unremarkable Juan Perez Perez? Is he the father of his children who are growing so fast he doesn’t realize it? Is he the son forever in search of the father figure? Is he a player? Is he capable of love?

As such, I conclude this review by saying that I found it quite clever from Salem to be able to introduce such serious questions amidst the sexual humor and the evolving intrigue throughout the book, and in this regard, I found his book quite unique. Because, I wouldn’t say that the intrigue is what holds our attention, nor the humor alone and the reactions JPP makes to the incidents and surprises popping up around him, but it’s a mix of all three rendered in a very entertaining writing style. I wonder the direction that Salem will take with his future books, as I suppose he is quite capable of playing more on the intrigue or more on the subjective elements or even spinning a complex love story in a mystery novel.

PS: In the “Thank You” section at the end of the book, I was surprised to read that Carlos Salem thanked, among others, a particular bookstore in Lyon, with the name of… “Au Bonheur Des Ogres“! I didn’t get the chance to visit it while I was there, but it’s cause enough for me to return back to Lyon.